Growing up in a family of scientists, it made sense that Audrey Shively would eventually find an interest in the subject matter. Her specific interest developed in elementary school.

Shively had a classmate with cerebral palsy. As her teacher explained what the condition is, and how the student was born with it, Shively was curious about why some individuals are born with certain disorders. It was the beginning of what has now become her primary research focus at the University of Missouri – genetics.

“I always enjoyed science in general, but this was the first time that I became really passionate about a specific area of study,” said Shively, a biological sciences major who will be a senior this fall. “Both of my parents work with the United States Geological Survey, so I was in the laboratory quite a bit when I was younger. While I enjoyed being in that space, it was very exciting to find something I knew I would like to pursue.”

Shively grew up in Columbia, and was part of a gifted education program offered through the Columbia Public Schools known as Extended Educational Experiences (EEE). That program allowed Shively, who attended Battle High School, to connect with genetics at a deeper level.

Among the various hands-on learning opportunities, Shively also read numerous genetic-related papers authored by professors at Mizzou with the hope that she could connect with at least one to see genetics work up close. She was able to meet with Jared Decker, an associate professor in the Division of Animal Sciences, whose lab studies population genomics and quantitative genomics in cattle.

“While we were able to only meet a handful of times, that experience was incredibly beneficial to me as I was getting more serious about genetics,” Shively said. “One of the most important skills he taught me, and one that I’ve carried through my time at MU, is the ability to read scientific papers. I also learned a bit about data analysis, which was something I hadn’t done before.”

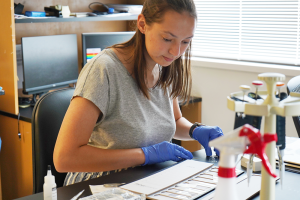

With limited research experience under her belt, one of Shively’s primary goals when she arrived at Mizzou was finding a lab where she could gain more experience and build on her interest in genetics. She found the perfect spot recently with Christian Lorson, a professor of veterinary pathobiology. The Lorson lab focuses on spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a devastating disease which affects one in 6,000 live births and is the leading genetic cause of infantile deaths, among several other projects.

Shively is working on one of those other projects, specifically focused on Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease. CMT causes peripheral neuropathy, which is weakness, numbness and pain caused by nerve damage that usually occurs in the hands and feet. Shively is working on Charcot-Marie-Tooth Type 2E.

“CMT is a disease that slowly progresses, and some are born with forms so mild that they don’t have symptoms until they’re older,” Shively said. “It’s oftentimes mistaken for simple signs of old age.”

Shively said Type 2E relates to the nerve fiber, or axon, that carries nerve impulses away from the cell body. She uses mouse models to study the disease. They watch the mice as they age and often stimulate the nerve to see what is happening.

“With this specific disease, the axon is not structurally sound,” Shively said. “It can’t send out signals to the muscles as well and that leads to muscle wasting and atrophy. However, the body knows something is wrong and perceives the issue as pain. We’ve been seeing this atrophy in our model.”

Shively added that while Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease isn’t terminal it can be detrimental.

“It’s a lifelong illness,” Shively said. “It’s also incredibly varied. There are mutations that we have pinpointed but there are differences from individual to individual, even with the same mutation. We don’t understand why that is, which is why this work is so important.”

Shively, who is also minoring in anthropology, was recently named a Cherng Summer Scholar. She said the timing was perfect as she had just started her research in the Lorson lab. A full-time, nine-week summer research or creative scholarship program for Honors College students, the program is supported by a gift from Peggy and Andrew Cherng and the Panda Charitable Foundation. Recipients receive a $7,000 award and access to a $1,000 project expense account.

“Getting the email that I had received the scholarship was exciting,” Shively said. “I knew I was going to be here this summer and working in the lab as often as I could. I’ll be able to do quite a bit more because of the extra funding I was able to secure through this program.”

As Shively enters her final year at Mizzou, she said she plans to continue to pursue research as an undergraduate and hopes to do the same at graduate school.

“I love the lab,” Shively said. “I’ve really enjoyed learning the skills that are required to do this work, and I’ve grown to appreciate diving into scientific papers. I’m still very interested in genetics, too, and plan to continue to look for opportunities in that space.”